Accountability

"OK, kids, time to pick up your toys!" Lethargic response. "OK, kids, as soon as all your toys are put away, we'll go to the park, but I only have an hour before I have to be back here!" Frantic cooperative activity.

What changed? Obviously, the kids saw they had a vested interest in vigorously getting the job done and, apparently, the parents had already established the fact that they always meant exactly what they said.

What vested interest do your students have to voluntarily participate in class discussion and, once the classroom layout is in place to facilitate it, what leverage do you have to ratchet up its intensity?

Hopefully the answer is two-fold. First, ideally, you are making regular oral participation both possible and desirable by:

1. motivating your students as you share stories with them about how speaking a second language has enriched your life (chapter 1)

2. respecting the natural language acquisition sequence (chapter 2), conveying meaning visually (chapter 2), cultivating 3-step thinking (chapter 4), delaying exposure to the written word (chapter 5) and developing in them linguistic reflexes (chapter 6) so that they are genuinely equipped to progress toward fluency

3. prioritizing substance over form with beginners and being effusive with praise (chapter 7)

4. being vulnerable and engaging your students in first person learning activities (chapter 9) so that they take an interest in the subject matter of your discussions

5. organizing your classroom to facilitate oral interaction (chapter 10)

6. and ensuring that the Four Pillars of World Language instruction are all in place (chapter 12).

There is also an extrinsic motivation that may lead your students to attain what you know is a highly desirable end (fluency), albeit through a less than altrustic method, namely, their concern for their grade. It is good for your students to be moved to engage in class activities for intrinsic reasons, however it is even better if both the instrinsic and extrinsic ones speak to them. Don't be ashamed to use their grade in your course as a tool to motivate engagement. Those children in the first paragraph, thrown into frenetic activity to ensure that they not miss out on a trip to the park, may well look around when the straightening up is done and find that the feel good about the orderly appearance of their room. In the same way, students driven to progress toward fluency out of a desire for a good grade are likely to thank you later for the learning that opened up a world of opportunities and relationships they never would have had without you.

So, practically speaking, how did I carry out the management, recording and evaluation of oral participation? First, I had to set up the "team" that would make thoroughly objective record-keeping possible and equip that team with a simple tool. This team was composed of three people, two of whom changed every day - the teacher, the computer operator and the recorder, with the latter two being students. As explained in the previous chapter, these two roles were important so as to allow my hands to be free to gesture or to perform mime and in order to allow me to maintain good eye contact with my students.

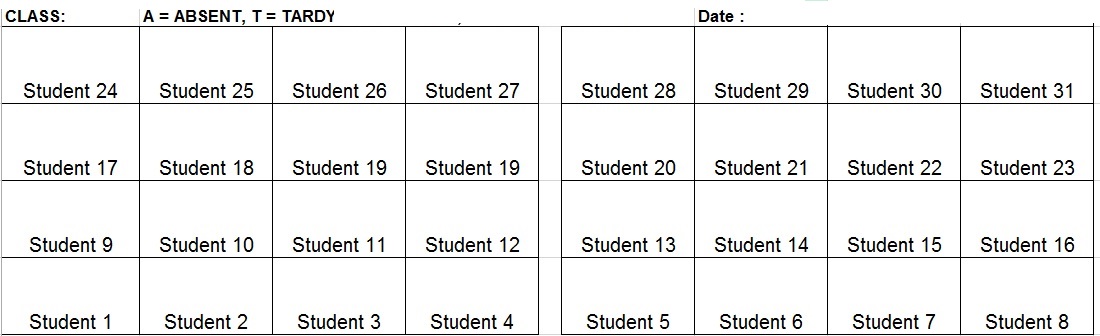

Wanting to rotate those two roles equitably, I would use the day's date to determine who was in those two roles. If the date were Monday, March 29th, I would count from the front left-hand corner of the classroom (from my perspective facing the class). The 29th person would operate the computer, situated at the computer control table, and the 30th would be the recorder of oral participation. The next day, March 30th, the roles would move ahead one seat. The 31st person would be the computer operator and the 32nd would be the recorder. Obviously, when the day's date was greater than the number of students in the class, after having reached the last student, I would continue counting by returning to the 1st seat. Therefore, in a class of 25 students, on March 31st, the person in the 6th seat would operate the computer...and so on.

With words and gestures, I would guide the computer operator to scroll and click on links of my choosing. As for the recorder, I provided him or her with the "Seating Chart and Record-Keeping Spreadsheet". In essence, it served as a class log for the day. The recorder would make note on it of absences, tardies and the specific tally of student participation.

If you download the spreadsheet, you will see that it provides enough space for the recording of the day's data for six classes, using the front of back of the page. Thus, you are seeing above one-sixth of the spreadsheet. The headings "Student 1, Student 2, etc." are to be replaced by the students' first names.

As for the types of oral participation activities we performed in class, they could be divided into three categories: structure drill, question/response and open-ended. "Structure drills" corresponded to a verification of ULAT structural exercises displayed on the screen in the front of the room. "Question/response" activities were those in which I would ask a question, usually of a factual nature, looking for a specific answer from the students. "Open-ended" discussions were those in which I would simply propose a topic that could receive any number of responses, no one of which was necessarily correct, and then allow the students to comment until conversation finally died down.

For structure drills, if we were studying lesson 6.3 on the imperative mood, for example, while working orally on the exercises found there with half of the class, I would send the other half to the computers to practice the exercises independently. Then, after 10 minutes or so, the two halves of the class would perform the activity that the opposite group had been doing. When both groups had had the opportunity both for guided practice with me and independent work on the computers, we would reunite as an entire class and we would review the exercises for oral participation credit. This is where the students' accountability for their use of class time came into play. When called upon to provide the correct answer to an item of the exercise on the screen, their response had to be perfectly credit or they would receive no credit. By contrast with the demand for perfection for a structure drill, any response to either a question from me (question/response) or remark in response to a topic I proposed (open-ended), factually and grammatically correct or not, would receive credit provided that it were comprehensible and on topic.

For question/response or open-ended discussions, sometimes it was necessary to judge the quality of the students' responses. For unusually outstanding remarks, I might choose to signal to the recorder to give the student double credit. Similarly, if I considered a student's remark to be either off topic or a largely mindless effort to accumulate points, I would wave off the point and the recorder would write down nothing. For example, if I was asking the class to retell me the story from a movie they have watched, and I was showing them an image from a portion of the movie, I would give no credit if a student merely said (usually with a smirk on his or her face), "He's wearing a red shirt." The students were not allowed to "rack up points" with inane comments, but only with those that advanced the retelling of the story.

How were students called upon to participate? First of all, their participation had to be voluntary. They had to take the initiative to raise their hand. How did I determine on which students I would call at any particular moment? Being very systematic about this is critical as it is imperative, particularly in light of the significant weight that oral participation plays in their grade, that the students recognize that you are being absolutely impartial and that all have an equal chance to participate. When the first opportunity for oral participation would arise each day, I would always look first at the computer operator to see if he or she wanted to response or comment. From that seat, assuming the student had not raised his or her hand, my eyes would move to the next person in the class order (see the seating grid above) and continue until I found someone with raised hand. When I wanted to elicit a further comment, I would simply indicate as much and would continue select responders from the next person in the seating chart. Upon getting to the last student in the back of the last row, my eyes would simply return to the first seat and continue with the same pattern.

Wanting both to help hesitant students to participate and to ensure that they all would listen to one another, I employed another technique at random moments. After a correct response, I would suddenly say "Repeat!", in the appropriate language, and my eyes would travel in the opposite direction, backward through the seating chart until I could find someone who was able to repeat correctly the answer that his or her classmate had provided. In such a case, since it was a matter of repeating another's correct response, an absolutely accurate repetition was necessary to receive credit. Following an accurate repetition, I would return in the order to the student having provided the original correct response and continue from there.

You may well be thinking, "This sounds ridiculously structured." I can't emphasize enough how important it is to have an invariable system, such as I have presented here, because you will occasionally be confronted by parents who recognize the heavy weight attributed to oral participation in your grading system and whose child, to escape accountability, will have told their parent, "He never calls on me!" Once you have explained your approach to the parents, their objection inevitably is dropped and their concern turns back to their child. If they want to continue to challenge the grade, all they can say is that their child is shy and doesn't like to speak in front of a group. At that point, I would simply say that the child will have to get over his or her shyness because it will impede the child's progress toward fluency, which is what the course is all about. The parent knows that the objection posed was a weak one and that generally ends the conversation.

From what I have shared thus far, you have probably gleaned that the students' oral participation grade was strictly a function of the sheer quantity of their comments and answered contributed over the course of the quarter or term. Among a group of grade-conscious students, cognizant of the heavy weight carried by oral participation in their grade, you can imagine that the competition to speak became intense. This is what I meant when I commented at the beginning of this chapter on a means of ratcheting up the intensity of oral participation. After a few weeks of such practices, I must confess that my students hand-raising reminded me something of the conditioning experienced by Pavlov's dogs. Even on those rare occasions when their oral participation was not being recorded, they seemed incapable of not raising their hands to respond to a question asked. And, to be honest, I would far rather they behave in that manner. It's a wonderful thing when students have been trained to help the teacher "carry the class" - far better than having them lounging back in their seats and daring us to try to move them to action. Besides, linguistically, they will end up being the greatest benefactors of intensive, competitive oral competition.

Here's one more word on accountability. Keep the pace of your lesson rapid. Don't allow the students to dictate how long the transitions will take from one activity to the next. Do not wait for them to be ready. Pause briefly and then dive into the next activity for which they are being held accountable. They will learn that you will not wait or them. For example, when performing the structure drill activity described above, you may remember that I would send half of the students to the computers to practice a ULAT lesson. As soon as I had finished working with the half of the class stationed with me, I would call out to those at the computer, always in the target language, "Log off and come back." After pausing for 5 to 10 seconds, and before most of those returning from the computers had been able to return to their seats, I would immediately say, "Number 1" and launch into the first item on the classroom screen that they were to say for credit. Those returning from the computers would already have their hands raised while walking and then jumping back into their seats. There was no dawdling. Remember the critical issues of time on task and repetition. Also, moving quickly from one item or activity to the next deprives the students of the "down time" when they are likely to lapse back into native language thought. Your rapid pace will protect your students from that undesirable practice!

Once the oral participation data has been gathered for that day from each of your classes, what do you do with it? That will be the subject of the next chapter, as I present you with the "Oral participation Evaluation Spreadsheet" - a device that was very complicated to create, but very simple to use, and which I considered the most useful tool in my possession after the ULAT program itself.