Undoing the Damage Done

As the weeks went by in the Dupré family's home, gradually a transformation was taking place in my ability to communicate with them and, unbeknownst to me, in the very way in which I thought as I spoke French. Returning to the example of how one could politely turn down another helping of food without eliciting hooting and laughter from the family, gradually I was making my loss of appetite known in a more accurate, natural and fluent manner.

How was this learning taking place? No, Mme. Dupré did not nightly tell me my options for expressing the state of my stomach, and she certainly did not write them down and post them on the wall by my place at the table. Rather, I observed and listened. I recognized that the meal was moving along toward its conclusion. I saw the puffed-out cheeks and the hands placed, one on the stomach and the other extended toward Mme. Dupré in a gesture clearly indicating "Stop!" The context clues were all in place. Then I would hear either "Non, merci. C'était délicieux, mais cela me suffit." (No, thank you. It was delicious, but that's enough for me.) Or possibly I would hear, "Merci beaucoup, mais j'ai déjà très bien mangé." (Thank you very much, but I've already eaten very well.)

No one needed to show me a chart of the conjugations of the imperfect or passé composé tenses, nor a diagram of the position of the indirect object pronoun. The context was clear and repetition reinforced the proper structure of the statements day after day, until responding to a food offering with one of those comments was the most natural thing in the world. The statements just rolled fluently off my tongue without any conscious thought. Little by little, context, repetition and seeing Mme. Dupré's comprehension were transforming the way that I thought as I spoke French. I didn't see text in my head, nor was I translating my remarks word-for-word from English. Whereas, during the first two weeks in the Dupré family's home, I would go to bed each night with a headache as a result of the convoluted five-step mental gymnastics I had to perform all day long in order to interact with them, now my conversation began to flow smoothly. Instead of disjointed sounds that I had to parse and translate, one at a time, I was starting to hear the music of the language by which entire thoughts are absorbed increasingly effortlessly.

This transformation was officially recognized by the family's head on a trip we took to a campground on the Mediterranean coast near the city of Cannes. Valérie, my 11 year old almost constant companion that summer, loved to play cards. Under the wilting heat of Provence, one moved about as little as possible at mid-day, which made a game of cards the ideal pastime. Valérie tended to win more than her share of games and I suspected that all was not taking place "according to Hoyle". One day, tired of being whipped by my diminutive exchange sister, I raised my voice a little too much and bellowed: "Mais tu triches, Valérie! C'est pas juste ce que tu fais!" (You're cheating, Valerie! It's not fair what you're doing!) My host father, awakened from his nap, came to remonstrate with me, informing me that one shouldn't talk like that. Then, having put me in my place, with a wry smile he added: "Mais quand même, il faut dire que ton français s'améliore pas mal." (All the same, I have to admit that your French is getting a good deal better.)

What was happening? I was listening, hearing statements made repeatedly in context, and without any recourse to printed text or to my native language, and then trying them out for myself. In the bigger scope of things, my stay with the Dupré family was gradually undoing the damage done over the course of five years of traditional French studies back in the U.S. in junior high and high school. Pity the students who sincerely want to learn a language, but who receive a traditional text-based foundation and never have the privilege of an experience such as I enjoyed that summer by which to reshape their teacher-damaged thought process!

*****

All right! Enough! Maybe you are growing weary of the derogatory comments about premature text-based instruction? The harm caused by teaching via translation is obvious enough, but just what is so damaging about an early exposure to the written language? After all, by middle and high school, students are already generally very effective readers of their native language. Surely a foreign language teacher can make use of their facility with reading one language in order to move their knowledge base ahead more rapidly in the second with the convenient tool of the written word! Isn't that true?

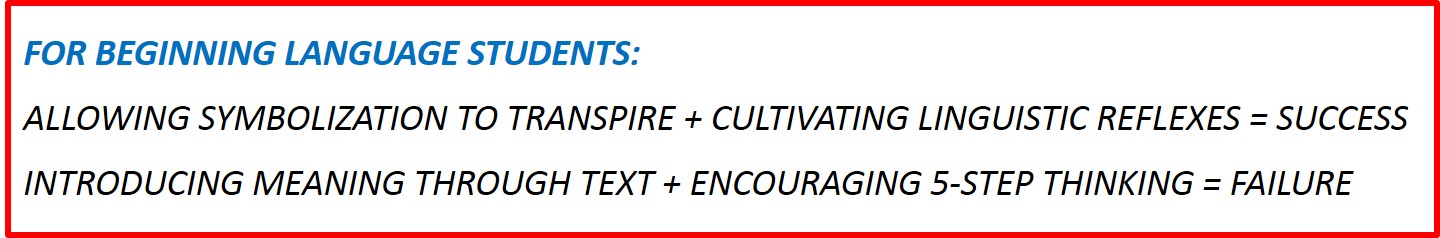

Of course, there is a place for reading and writing in the world language classroom. But I have been bad-mouthing only the premature exposure of it. The question is what constitutes premature exposure? Simply put, premature exposure to the written word occurs when teachers introduce a word's written form prior to "symbolization" having transpired in the students' mind and before its authentic pronunciation has become the norm in the students' speech.

Now, what is "symbolization"? Symbolization refers to the process by which our brain associates a word with its meaning. Let's take the verb "to sled" as an example. Likely, when we were very young children, we were exposed to this word while standing in the cold near the foot of a sledding hill. (We may have heard it said prior to that moment, but it was devoid of meaning for us.) Our parents said to us, "Do you see them sledding?" Depending on how young we were, they may have repeated the statement in modified form. "They're sledding down the big hill!" Then we heard the infinitive form when we were asked, "Would you like to sled?" We saw the sled start its descent at the top of the hill, build up momentum as it hurtled downward, flash past us in an instant and then glide slowly to a stop. Through repetition of the experience, as more and more sledders flew by us, and as our parent repeated the word in that context-laden environment, its identity, meaning and pronunciation were reinforced, and even more so when we took our first sled rides that day.

In the following weeks, we ourselves began using the verb "to sled", likely to incite our parents to let us repeat the experience. At first, before speaking, we may have hesitated while we recalled an inner video of our initial exposure to its meaning, seeing the entire descent of a sled and its rider from the top of the hill to our left until they glided to a stop to our right. However, as we began using the word in speech, you can be assured that our mind did not replay that entire inner video before bringing the word to our lips. Instead, it assigned a key still image from that inner video sequence to forever represent for us the idea of sledding, probably the most exciting moment when the sledder first flew past us.

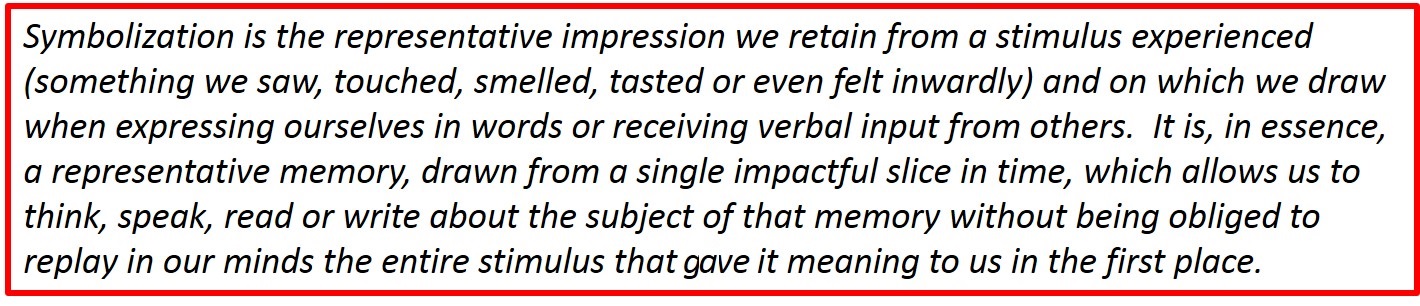

Symbolization, therefore, is the impression we retain from a stimulus experienced (something we saw, touched, smelled, tasted or even felt inwardly) and on which we draw when expressing ourselves in words or receiving verbal input from others. It is, in essence, a representative memory, drawn from a single impactful slice in time, which allows us to think, speak, read or write about the subject of that memory without being obliged to replay in our minds the entire stimulus that gave it meaning to us in the first place. How do we know this transpires? When that three-year-old first heard and then began using the word "sled", could he read or had he ever written? Did the pace of his or her speech allow time for the entire inner video to be replayed before uttering the word "sled"? Of course not, on both counts.

Above you see the ULAT's presentation of the concept "to wash" in Spanish. The approach used in the ULAT respects the symbolization process. In presenting a verb, for example, the student first sees a brief video clip of an action with associated sound. Next, a gesture is performed that represents that action. Finally, a key still image from the video is extracted which will thereafter always represent the verb when the student is led to use it in speech.

Is symbolization only an activity that occurs with elementary concepts during our youngest days of childhood? What happens when a more sophisticated word, such as "quizzical", is first introduced to us in printed form later in our adolescence or young adulthood? Once an adult explains the word's meaning to us or once context makes it clear, for that explanation to have any meaning, we are obliged to view inwardly the image of something we can understand, namely, the somewhat twisted facial features of a person who is intrigued by something that he or she does not yet know or fully grasp. The absence of such a clear image means that the explanation we received, or our comprehension of that explanation, was insufficient. (As a consequence, we may find ourself using "quizzical" as a synonym of "confused", "troubled", "pensive" or any number of other words for which it is not an exact match.)

Part of a lesson created by the ULAT's author early in his teaching career. This is precisely the wrong way to introduce students to a language's structure: teaching beginners via translation and the printed word, removing the opportunity for symbolization to take place and training students to explain a language, not to speak it.

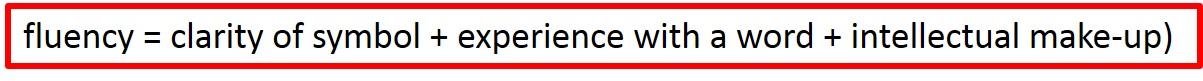

Provided that our comprehension of "quizzical" is sufficiently clear, our inner processing of the word occurs in one of two forms - either from inner symbol to outward expression (speaking or writing) or from outside stimulus to an inner vision of the symbol (listening or reading). Of course, the almost inconceivable capacity of the brain causes these processes to occur at such a speed that we are not naturally cognizant of our use of symbolic thought until a lack of clarity or familiarity obliges us to slow down the process and consciously envision the word's meaning in symbolic form.

In speech, remembering the description of a quizzical face, we are able to reproduce the word orally at a rate of speed directly proportionate to the clarity of our inner symbol (the face and its twisted facial features) plus the frequency of our experience with the active (speaking and writing) and passive (listening and reading) use of the word plus our particular intellectual capacity to formulate speech. When listening, the same factors impact the speed at which we process meaning. The only difference from speech is that the initial stimulus comes from without, as opposed to being initiated by an inner desire to be heard and understood. When reading, we first see the letters and then, at a rate once again dictated by the above-mentioned formula (clarity of symbol + experience with the word + intellectual make-up), we arrive at a comprehension of the printed word. When writing, our mind moves from the symbolic concept we want to convey to the word in printed form that we are about to transcribe. In all four cases (listening, speaking, reading and writing), our mind makes use of symbolization. Were that not the case, our native speech would approximate the halting, stilted efforts of foreign language learners in most world language classrooms.

Our ability to produce speech depends upon our comprehension of a word, thus the clarity of the inner symbol we have assigned to it, the frequency and intensity of our past experience with that word and our particular intellectual capacity to move from inner visualization to outward expression and to recombine words to form complex structures. Removing or impeding the symbolization process by replacing stimuli perceived by the senses with text that represents those stimuli, and by adding the supplementary complication of the need for translation, results in slow, stilted, awkward speech and sometimes even embarrassing miscommunication.

Aha! Now we are starting to "revenir à nos moutons" (get back to the question at hand). What does all of this talk of symbolization have to do with our methods of foreign language instruction? Everything. Remember our definition of "premature" exposure to the written word - introducing a word in written form prior to symbolization having transpired in the student's mind and before its authentic pronunciation has become the norm in the students' speech. The use of printed text to introduce words and their meaning lies at the very heart of failed language teaching methodology. Its antithesis, making use of symbolization and the development of "linguistic reflexes", which will be explained in the next chapter, is the critical key that unlocks the path to student success and teacher satisfaction. Why is this?

First, let's look at the undesirable approach. One must recognize that the written word is frozen in time. This means that students can look at and consider it at their leisure. This reality stands in stark contrast to how authentic oral communication takes place. While standing on an urban sidewalk, waiting for the next bus to come, if one is approached by a man holding a cigarette who asks: "Vous avez du feu?" (Have you got a light?), such a situation calls for a reflex response and not a leisurely consideration of the vocabulary and syntax the man has employed. Such a pathetically academic approach to communication as the latter one would result in the man walking away in disgust. Better to respond with less than grammatical perfection, yet in a comprehensible and instantaneous fashion, than to be paralyzed by the need to analyze.

Yet, such paralysis is the very response we set students up for when text-based instruction occurs prematurely. Why do I say this? When a word is first presented to them in written form, students can analyze the word at great length, being free to come up with associations with their native language to aid in its retention. Not willing to forget it, particularly if they know they will soon be held accountable to reproduce it in written form on a test, they repeat it to themselves over and over, either aloud or in their mind. They return time and again to the word association they have created with English so as to be sure not to forget it. For example, at the very beginning of their first year studies, they learn the verb "habiter", which means "to live". (Yes, I know I'm translating. I am not teaching you French. Besides, some of you are Spanish teachers.) If they are native speakers of English, the first thing they do, when they are told what it means, is obviously to associate it with the verb "inhabit". Next, they roll it around on their tongue or in their mind. If this occurs before sufficient oral repetition has taken place, or very extensive phonics instruction (unlikely at that point of their studies), they will inevitably make use of the English phonics system. They will pronounce the "h". (For the non-French teachers among you, I hasten to add that the "h" should be mute.) They will incorrectly pronounce the "a" as one does in the English word "hat". They will make a dipthong in pronouncing the letters "er" whereas the verb ending should be pronounced as a single vowel sound. In short, they will establish their own norm for the word's pronunciation, on the basis of the English phonics system, thus deepening the native speaker's disdain and amusement at their efforts to speak.

Consequently, when the time comes to try to use "habiter" in conversation, three very negative things take place. First of all, to recall its identity, the students short-circuit the natural form of thought, which involves an unspeakably rapid flow of images in the brain, by picturing in their minds the letters of the English word "inhabit". Secondly, they are slowed by having to envision the printed translation of the word "inhabit" in the target language: h..a..b..i..t..e..r. (I can hear some of you saying to yourselves right now, "Oh, that's but a trifling matter. That takes place so fast!" That is like saying that the TGV, traveling at 200 MPH, is really "fast" just like a spacecraft leaving earth's atmosphere at 25,000 MPH is really "fast". The halting way in which traditionally taught language students speak, when obliged to speak extemporaneously - if that ever occurs - is incontrovertible proof that there is quite a difference between "fast" and "lightning fast".) Thirdly, as mentioned above, students apply the English phonics system to the word, since no other normative pronunciation has first been established. Once these undesirable patterns of thought and practice are established in beginning students, they become the faulty foundation on which the rest of the students' linguistic edifice will precariously repose.

Now, let's look at the desirable approach and its outcome. When we present the meaning of words to our students by means of sensory stimuli - the most common being sight - they are largely delivered from the danger of word associations with their native language and are not tempted to employ the English phonics system in trying to imitate your verbalization. Provided that the word's meaning is made sufficiently clear by the expressive and uninhibited world language teacher and that its corresponding pronunciation is sufficiently drilled to the point of forming in them a linguistic reflex (see the next chapter), their speech is free to increasingly replicate that of the native speaker, because they have been trained to think in the three-step process (desire to inner verbalization to outward expression) that typifies authentic native speech.