Three-Step Speech

It was a sunny Sunday afternoon in a small village of northern France about five miles from the walled city of Laon. It was only my second Sunday in the home of the Dupré family and, as a 16 year old summer exchange student, I was still learning the basics of French mealtime habits and vocabulary.

The Dupré family and their American guest

I had already gleaned that the Sunday mid-day meal was a big deal in France, as I watched Mme. Dupré race back and forth from the table to the kitchen, clearing off the dishes from one course and bringing on yet another set for the next culinary delight. The meal and conversation had already gone on for over an hour when Mme. Dupré turned to offer me yet another helping of ratatouille. As I already stood 6'5", far taller than the rest of the Dupré family, and was as skinny as a rail, Mme. Dupré had taken it upon herself to stuff me with as much food as she could with each meal. She apparently feared sending me back to my mother in the States looking as gaunt as I had upon my arrival in their home.

This time, however, I could not conform to her wishes. I was absolutely full. As she reached out toward me with a dish of the vegetables that the marauding local wild boar had failed to steal from their garden, I needed a few moments to collect my thoughts before responding. My ability to interact with the Dupré family was anything but spontaneous at that early point in the summer. After first taking stock of my stomach's feelings, I next needed to inwardly verbalize, in English, what it was that I wanted to tell her. Secondly, because my training in French had been delivered in a text-based manner (vocabulary presented in written form and with an emphasis on translation), I was obliged to envision in printed form the statements, "No, thanks. I am full." Again, this second stage of inner verbalization of text was necessary because I needed to "see" inwardly the French translation and the form of each word as it had been presented to me and as I had retained it. Fourthly, while Mme. Dupré waited patiently for my response, leaning on the training received from Mr. Carson, Miss Majors and Mr. Kaprinoff, I carefully translated in my mind the five words of my intended answer. "No = Non, thanks = Merci. I = first person singular personal pronoun = Je, am = first personal singular conjugation of the infinitive "to be" = suis, full = ?. Hmmm. Oh, wait! full...like a bottle = plein (masculine singular form of the adjective)!" Finally, with a certain amount of pride (after all, here I was speaking French in France while most of my friends bαck home were just lying by a pool or watching reruns on TV), I responded, "Non, merci. Je suis plein."

Upon my response, the rest of the family burst into sudden laughter that went unabated for what felt like a minute as they sought unsuccessfully to regain their composure. Even Mme. Dupré, always my ally in the family and patient with my linguistic weaknesses, struggled to hide a smile. As the hilarity subsided, in her most indulgent of motherly tones, she explained to me that I had just communicated, "No, thanks. I'm drunk." In fact, had I been an animal, what I had said would have meant, "No, thanks. I'm pregnant."

Where had I gone wrong? How had my grade school instructors betrayed me? The answer lay in what they, and likely most all of the language teachers of their generation, saw as their objective in the training of their students. Their goal had been to enable us to explain how French was structured, reasoning that if we could recite the rules governing its structure, correctly reproduce the conjugation charts and restate in English the meaning of French vocabulary, then certainly it was logical that we could speak the language, having all of the tools for fluency at our disposal.

The fallacy in their thinking was reflected in the five-step thought process through which I had passed in formulating my laughter-inducing response to Mme. Dupré. I had performed a series of mental gymnastics that first year teacher, Mr. Carson, had set in place years earlier by his traditional methodology. Then, like deepening the groove in the vinyl of a long-play album with a weighted record player needle, Miss Majors built on the flawed foundation with nightly translation assignments.

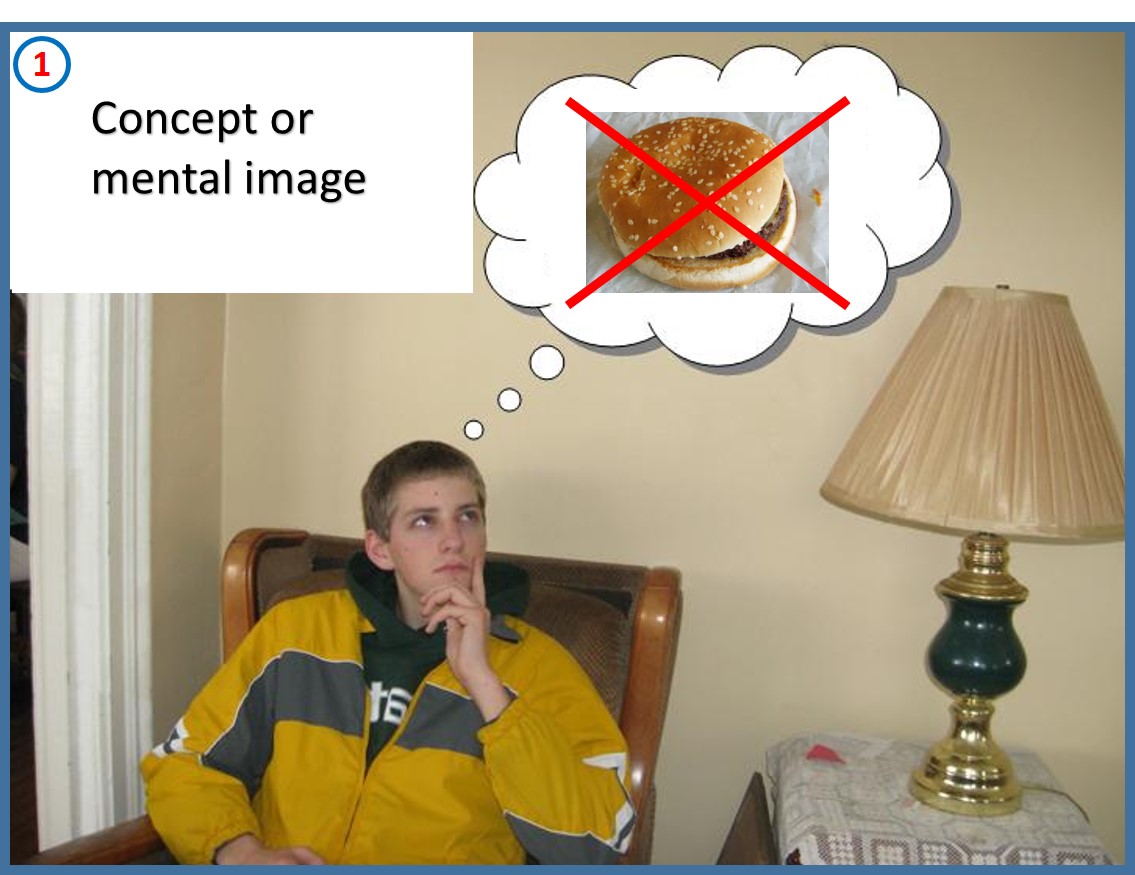

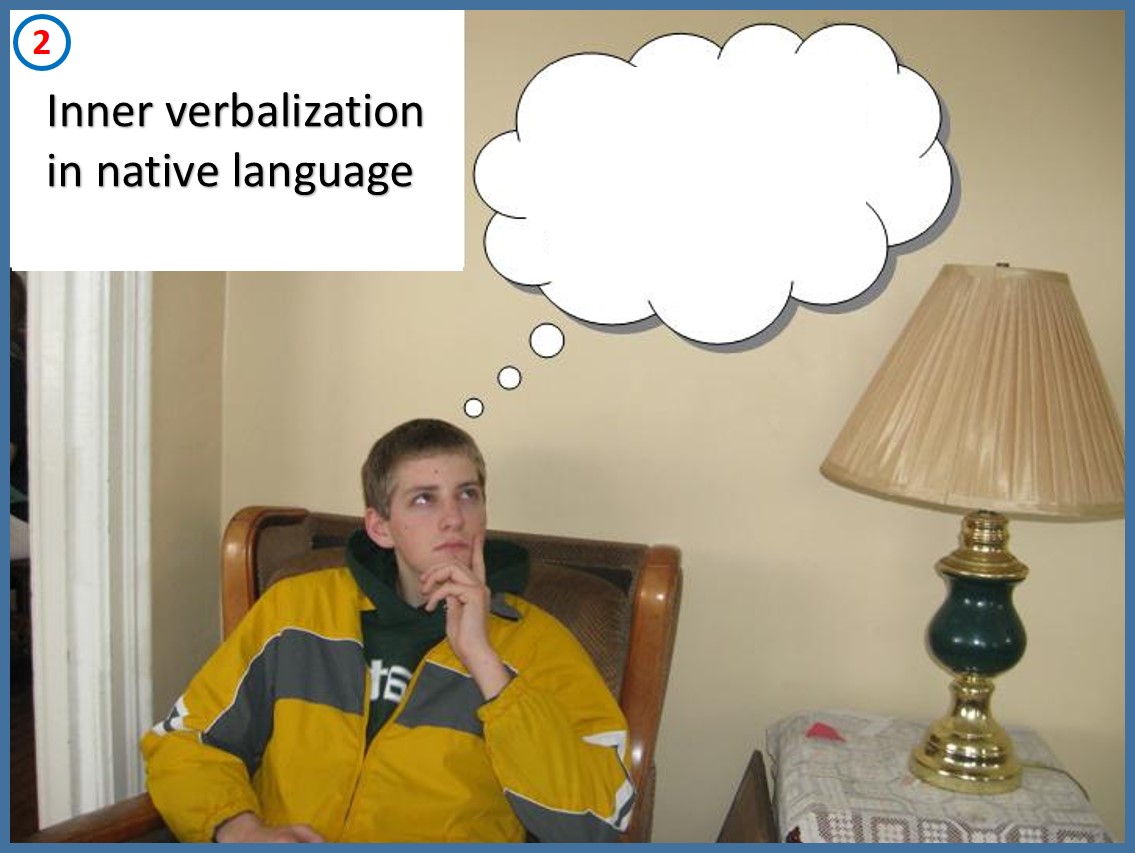

The problem that it took all summer to finally undo was that native speakers of a language do not think and speak in a five-step process. Rather they express themselves in three steps. First, even though it takes but a nanosecond and occurs wordlessly, they become aware of a message that they want to convey: an observation, a feeling, a question, a request, etc. Secondly, in an equally infinitesmal instant, they inwardly verbalize their message. Finally, they articulate aloud that which they want to express.

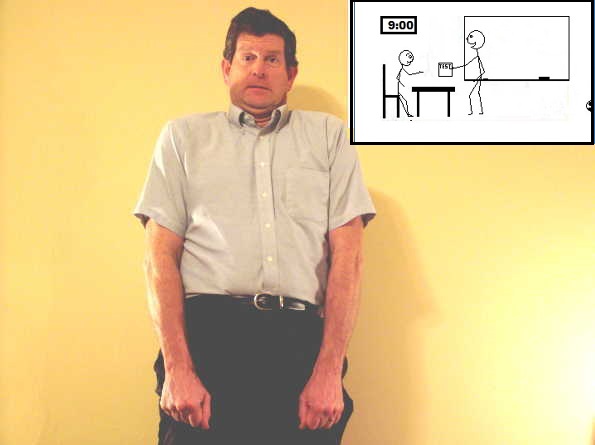

The destructive five-step thought process produced by premature text-based instruction

Therefore, what is the difference between the thought process of the native speaker and the second language learner that results in inauthentic, awkward, stilted, slow and sometimes embarrassing speech on the part of the non-native? It resides, of course, in the additional step of inward translation needed by the inappropriately trained non-native speaker. It is that step which slows speech, as learners are obliged to pass their thoughts through the grid of their native language, thus deeping each time the "groove" connecting one language to the other. It is also that step which produces awkward and even embarrassing speech, since translated vocabulary lists encourage the establishment of a one-to-one correspondence in the students' minds between the native and second languages, whereas words in the target language often carry a multiplicity of meanings in varying contexts that are not replicated in the students' native language (i.e., "A bottle is full" and "I feel full.")

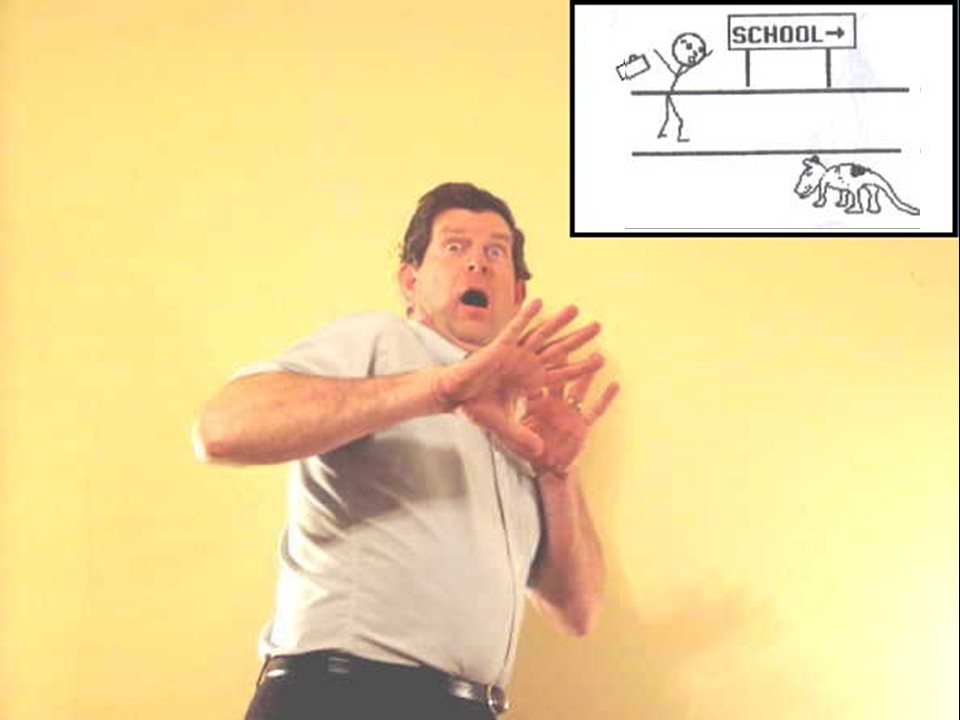

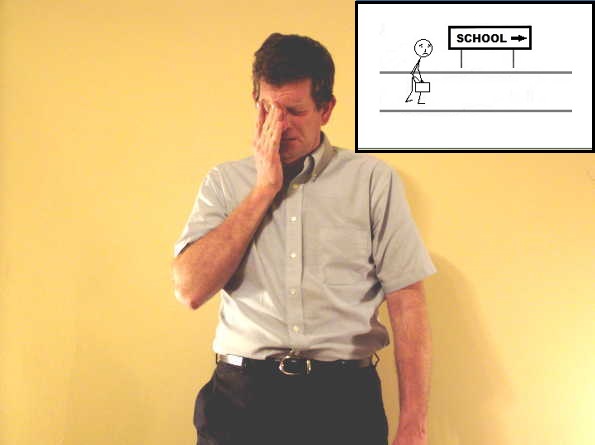

Does that mean, therefore, that fluency only requires language instructors to eradicate translation as a teaching tool and translation exercises as an assignment? Well, that's a good first step, but bear in mind that such a measure is not as simple as it sounds. It implies another more profound change in pedagogy. It means that it will be impossible at first, before students possess the vocabulary knowledge and know the rudiments of the new language's basic structure, to explain the meaning of words to them with other words in the target language. It will thus require instructors to represent the new word's meaning in some visual fashion, either by means of a drawing or, more likely, by acting out its meaning. It also suggests that the students' retention of the word's meaning will require a means of consistently visually representing that word and then reinforcing the link between the thought and the visual cue. Teachers will not want to have to perform an extensive mime each time the word slips a student's mind. Additionally, as will be discussed in a later chapter on symbolization and the establishment of linguistic reflexes, in order to develop fluency in their students, teachers need to rapidly move them from cues requiring an entire pantomime to those consisting of no more than an image that can be displayed for a split second.

Removing the unwieldy third and fourth steps of inner translation from the students' thought process by conveying meaning in a visual fashion also suggests something about language teachers themselves. At least to some extent, they must be actors and, better still, actors with a dash of clownishness in them - not enough to make themselves ridiculous, but just a "dash" to lighten the mental tasks that otherwise make for some heavy cognitive activity on the students' part. Self-conscious and inhibited language teachers place a damper on their own results with students and an unnecessary hurdle in the path to their students' attainment of fluency.

The ULAT's author using facial expressions, mime and drawings to convey the meaning of the words "scared", "sad" and "tense"