Classroom Layout

Classroom layout? What does this have to do with facilitating oral interaction? Possibly more than you can imagine. When you have exciting news you want to share with a friend about a new significant other in your life, do you enter a restaurant and have one of you sit at a table at the back of the dining room, while the other sits up front by the windows, and then call out your news one to one another from across the room? Or does your friend sit with a stranger at a neighboring table and cast sideways glances at you as you share your excitement? When your time is limited, and you have a lot on your heart to share, do you show up late and then spend an inordinate amount of your time consulting the menu and visiting the restroom, leaving just 5 minutes for conversation? Knowing that you want the maximum opportunity to share your news with one particular individual, do you invite five other friends to join the two of your for lunch that day? And when the two of you are finally alone and ready to talk, do you provide your friend with just the vaguest of details regarding that new person in your life, leaving most details for your friend to wonder about or imagine?

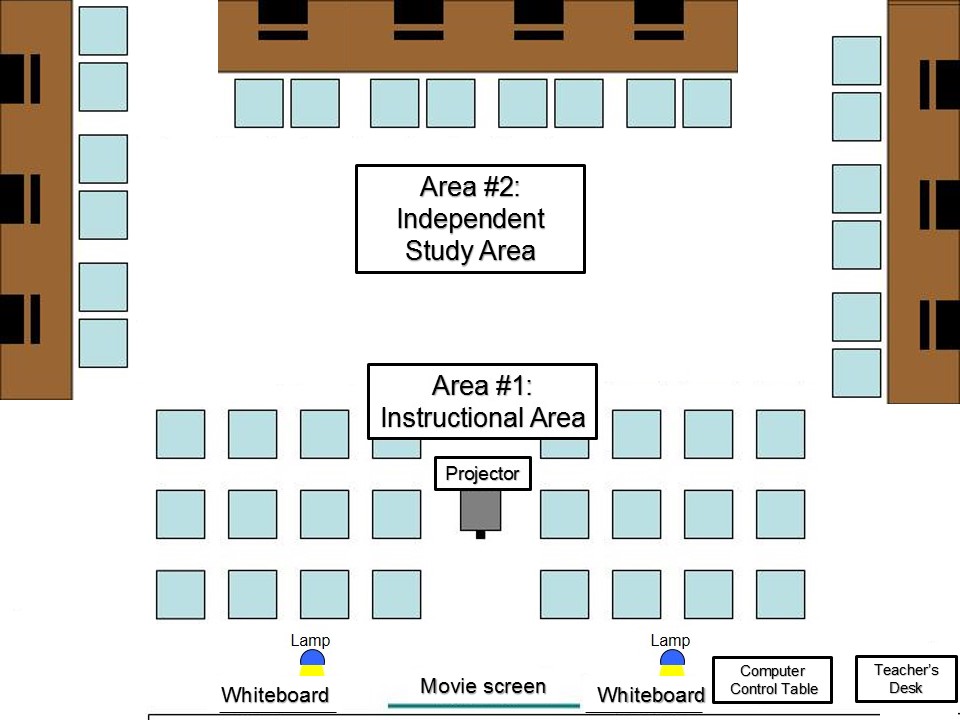

Of course, you do none of the above, but these things we do, in essence, when we don't organize our classroom to prioritize intensive oral interaction. First, let me show you and describe the layout of the classroom where I spent the last nine years of my teaching career.

The first logistical principle to respect when organizing your classroom for conversation is that of "proximity". Effective interaction does not take place over great distances. As elementary school teachers know, who seat their flock close by on the carpet or on a rug to hear a story, proximity promotes engagement and a feeling of togetherness. You want your students to feel involved in the on-going discussions in class. You want them to be close enough to feel personally implicated by the topic you are promoting, close enough to feel that they are carrying on a genuine conversation with you and close enough that they can see your facial expressions and how you are forming the sounds of the language. For that reason, the first thing I did was to remove desks from my classroom and to replace them with simple chairs, which correspond to the light blue squares in the drawing above. Desks take up far more space and push the last rows of your students way to the back of the room.

The second principle is that of "focus". I eschewed the temptation to seat students in a semi-circle or at tables facing one another. At first glance, seating them in rows, facing the front of the classroom and the movie screen, might seem counter-productive to oral interaction. After all, pairing students up with the student sitting across a table from them could seem like an ideal means of promoting conversation. Seating them in a semi-circle would give them a good view of the face of the student speaking at the time. However, I had to remember that it was I who needed to serve as their model for speech and pronunciation. They could always turn sideways and see most of their classmates but, to the degree that their frontward focus deviated from the axis of a straight line between them and me or them and the movie screen, to that same degree would their distractions increase. A partial deviation from that axis would result in a partially distracted student, which was no small matter when, through my gestures, facial features and acting, I was constantly seeking to convey meaning to them.

The third principle is "time on task". Time on task, if paired with sound pedagogical practices, is one of the great predictors of significant learning. All successful athletic coaches are very aware of the importance of time on task as it relates to maximizing the repetitions that result in skill development. As I recall the junior high school basketball team on which I played ("played" being a euphemism for "sat on the bench"), one of the poorest uses of practice time was the lay-up drill in which two lines were formed, one for those waiting to shoot a lay-up and the other for the rebounders, who would gather the ball in after it was shot and pass it to the next shooter. If there were twelve players on the team, there were two at a time actively engaged in performing some activity and ten players standing around waiting their turn. It was a terrible waste of time - a precious commodity for coaches and teachers alike.

Just as you do not want distractions to decrease your students' involvement with you as their model, you do not want to allow a poor use of class time to diminish the repetitions of the skill which is the emphasis in your class that day. To that end, I did all in my power to allow students to begin practicing their lessons as soon as my brief opening monologue was completed and to enable rapid transitions throughout the class period from one activity to the next.

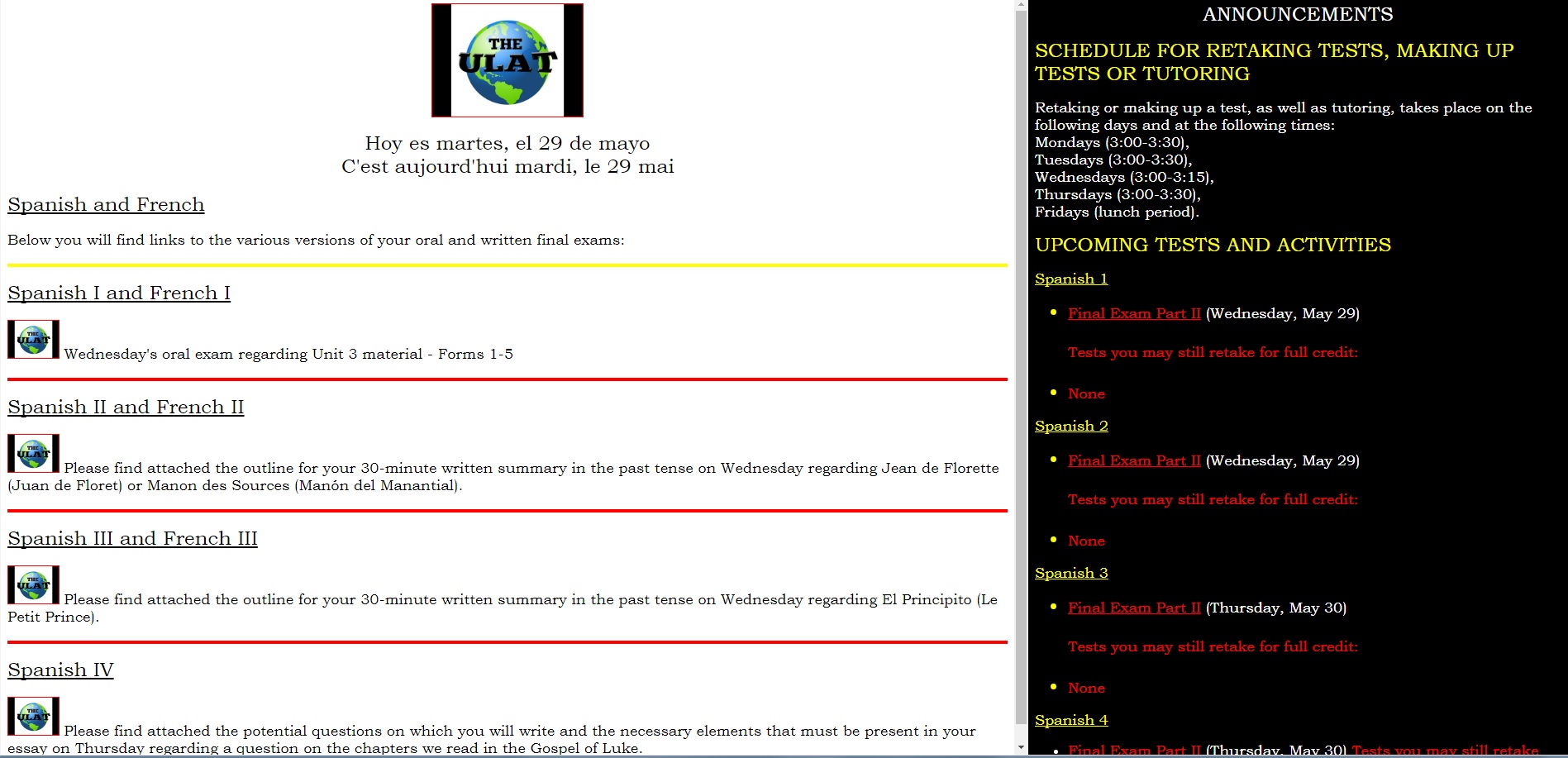

The daily schedule you see below was displayed on the classroom screen as the students entered the room (and was the only English they would see or hear that day). On the left would be the activities we would be doing in each class. By clicking on the ULAT logo, the students would be taken directly to the lesson or review materials on which they were to work while at the computers. On the right they would find all of the pertinent class information, such as make-up days and time for testing, upcoming tests and, if they scrolled down, they could read behavioral expectations as well. If time were going to be exceptionally short to accomplish my objectives on a particular day, as soon as enough of them were in the room, and even before the bell sounded, in the appropriate language, I would simply say, "Group A, to the computers!" and half of the students would head there to begin their activities. The browsers on the computer were all set to open to this daily schedule, so the students could get right to work - all to the end of maximizing time on task and repetitions of the day's skill objectives.

The fourth logistical principle to respect, if one wants to maximize the chance for students to participate orally, is that of "concentration". In a class of 24 students, the individual student can feel minimally involved in the class discussion. Cut the group into two parts, assigning half of the class to work on the computers and only 12 of them to talk with you, and that same student's sense of responsibility to participate is at least doubled.

By this time, some of you may be thinking that having ten computers in the classroom is an unsual luxury. First of all, they were used desktop computers, as were the monitors, thus drastically cutting their cost. They were each equipped with "splitters" and headsets allowing each computer to facilitate two students simultaneously. In my case, their presence was so indispensable that I spent the quasi-totality of my world language budget each year on the purchase and maintenance of this equipment (and even kicked in a little of my own money), because of the fifth principle, which is "instructional multiplication". This rather grandiose term merely means that I wanted to maximize the the number of sources simultaneously available to teach. I wanted my students to be able to talk with me in person, to hear me and interact with me on the computers and, at times, to receive input from a teacher's aide. In essence, I was multiplying myself in order to be able to converse directly with ever smaller numbers of students, while having the remainder of the class gainfully occupied with meaningful learning activities, thus intensifying the oral participation activity.

The final principle I respected in order to foster oral interaction was that of "stimulus augmentation". When Mr. Kaprinoff read "Le Roman de Renard" to us, we had no visuals to aid our comprehension, save the one-inch square drawings that he would occasionally show us as he walked around the room with the book turned in our direction. Too distinguished to prance about and act out the story's events, seeing our incomprehension, he would eventually say, "You don't understand? Well, let me see if I can help you." He would then lapse into a summary in English of the passage just read.

A photo of my actual classroom taken from behind the bank of computers. Notice the slightly darkened room, the lamps illuminating the whiteboard, the computer control table, the use of chairs as opposed to desks. Notice also the almost total lack of décor. (I couldn't do everything!) The room is actually brighter than usual because the blinds on the left side of the room were not closed at the time the photo was taken.

Look again at the classroom's layout. You will notice that there is a "computer control table" to the right of the screen, connected to the overhead video projector, and two lamps directed at portions of the whiteboard on each side of the screen. Not surprisingly, as the discussion would be taking place, the ULAT lessons would be displayed on the screen, but I would not situate myself at the control table. Rather, knowing that the lesson would have to be scrolled, that links would need to be clicked on and that pages would have to change during the discussion, I would teach from the area to the right of the screen and have one of my students sit at the control table to manipulate the computer, thus leaving my hands free to gesture and leaving me free to maintain good eye contact with the students.

Why the lamps? So as to ensure the clarity of the image on the screen and to encourage the students to focus on that image, I would dim the overhead lights, leaving only a bank of lights on in the rear of the room. The lamps, therefore, illuminated the white board on each side of the screen so that I could use those spaces either for illustrative drawings or for text when a written exercise was being studied. In sum, working with a small subset of my students, I wanted them to see a large, sharp image on the classroom screen, augmented by my facial expressions, gestures and drawings, and accompanied by my voice or by the computer's sound system.

Proximity, focus, time on task, concentration, instructional multiplication and stimulus augmentation? It sounds pretty intense! Indeed, I wanted the layout of my classroom to help me give my students a bit of a wild ride. Rather than lounging back in their chairs and saying, "Teach me. I dare ya!", I wanted them sitting on the edge of their seats and competing with one another to be allowed to participate orally. To accomplish that goal, there was one more element that I needed to put into place. You'll hear about that in the next chapter.