The ULAT

It may be difficult for today's teachers to remember a time when they could not create their own presentations composed of videos, images, sound and text, and then put them online for their students to work with at home. I am old enough, however, to remember a time when photocopying materials was about as high tech as one could go.

Therein lay my greatest obstacle. I had adopted new pedagogical principles, whose initial emphasis was exclusively visual and aural, about a decade before I had the technology and knowhow to create corresponding study materials. The principles on which I had settled could be respected in class when I was there to act, speak, draw, gesture and point. However, how was I to enable my students to study outside of class in a way that would respect those principles and therefore not undo the most important of my goals - training students to think as does a native speaker? How could I convey meaning visually, without any recourse either to the printed word or to translation when all of the technology I had at my disposal was a typewriter, photocopier and tape recorder? As you will see, the task wasn't impossible, but the result would be unattractive and less than dynamic.

For five years, I limped along, having excellent results in class, but finding it all but impossible to give my students materials to study at home. Things didn't change for a while after my family and I moved to northern France in 1985. I did almost all of my English teaching for the Chamber of Commerce, working in businesses with executives who needed English in their line of work. As I was working with adults, all of whom had gone to college and had already received years of text-based instruction in English, augmented by a heavy dose of translation, there wasn't much I could do to rebuild a proper oral foundation in the scant hour or two that I was with them each week.

I was anxious to get back to the principles that had brought me success while teaching French in the States. I was finally able to do something about it in 1990 when I began my own private language teaching business in Ronchin. There I would be working with the general public, many of whom had almost no knowledge of English whatsoever.

Wanting to capitalize on the tabla rasa that I was being given, but still limited in my technology, as I would only see them twice a week, I determined that I would create review materials that would help my beginning adult students develop a proper foundation of oral abilities. Throughout the majority of the first year of study, with no recourse to printed text or to translation to the learners' native language, those materials would need to convey meaning visually and in tandem with recorded sound.

By the early 1990's, the gadgets at my disposal had increased slightly and had experienced one important modification. In addition to a tape recorder and photocopier, friends from our home church had supplied me with a high-speed tape duplicator and, most importantly, with a Macintosh SE computer to replace my former reliance on the typewriter.

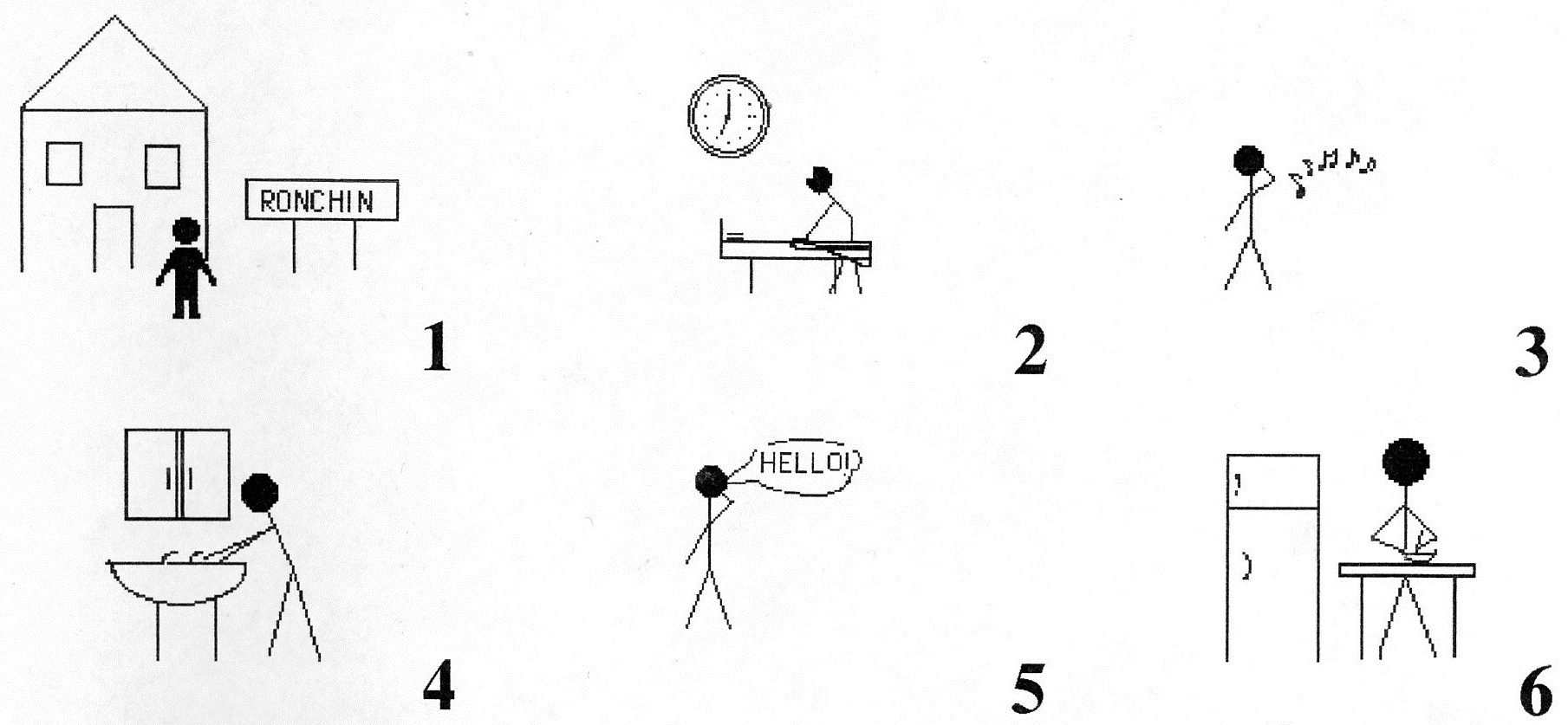

I used the computer's Paint program, to create crude stick drawings of characters performing the 60 most common verbs and daily routine activities, or representing certain physical traits and emotions. Each drawing on the 200-plus photocopied pages was numbered so that it could be referred to specifically and described by the recording on the cassette tapes that each student received. The resulting product was very amateurish in appearance, but I was now headed in the right direction.

Stick figures representing the first of the 60 most common verbs: live, do/make, listen, wash, say/tell, prepare

The curricular tide had begun to turn with the creation of my image-filled English manual. For me, my curriculum creation efforts would become a virtual tsumani following an amusing and eye-opening comedy of errors one day at the site of my new job for the Chamber of Commerce in St. Quentin, France.

In the mid-1990's, the Chamber of Commerce had just obtained its first multimedia language lab. When "experts" from the lab's manufacturer came to demonstrate to us its educational applicability, during an embarrassing orientation session, it quickly became apparent that the trainers themselves scarcely knew how it functioned and even less how we might make use of it. Apparently, the more knowledgeable support team was busy providing training elsewhere in France at that moment and the manufacturer of the language lab equipment, hoping to cover up that fact and yet still receive a handsome sum for providing training, had sent along some largely incompetent imposters to train us. My boss became furious when she realized that the trainers didn't really know how the equipment worked either.

Nonetheless, I went outside that day with my head spinning following that first introduction to the concept of "multimedia". As was my wont, I strolled across the spacious lawns of the Chamber of Commerce building to stand in line with other workers at a converted camper (une baraque à frites) out of which a wide variety of dishes was being served, all having French fries as the base. I mused about what I had just seen. The bumbling technical team had apparently been able to show us that these computers could be made to play a recorded sound when clicking upon what must have been a hyperlinked phrase - the first hyperlink I had ever seen.

One of the symbolic gestures indicating that the student is merely to listen

While awaiting my turn to order, a thought suddenly struck me. By combining images and sound, and still respecting the principles on which my teaching had come to repose, could I not create a multimedia program that could teach any language to a learner who spoke any native language? Could I not create lessons, replete with images and linked to their corresponding sounds, on which the learner could click and hear the word while inherently perceiving its meaning from the image itself with no need for translation? Moreover, without needing to change the lesson in any way, by recording a native speaker saying the same statements in his own language, and then by replacing the original sound files with the new ones just recorded, I could make the identical lesson teach a new language. In addition, to facilitate any person in the world who wanted to use the program, I could use "symbolic directions", images that would clearly convey by their appearance what the learner needed to do in each section of a lesson. In this way, instructions need not be given in English, or any other single language, and thus render the lessons unusable to whomever did not know that language.

All of these reflections took no more than 5 minutes, as did my wait for my French fries, but that moment in line had radically altered how I would spend much of my remaining professional life. I could not begin immediately in the pursuit of that vision, because I still lacked the tools and knowledge to make the ULAT a reality. I still had to teach myself HTML, website construction, video creation, how to use PowerPoint, how to digitalize and edit images and recorded sound. The creation of the ULAT would begin in earnest upon the Nesbitts' return to the United States and as the new millenium dawned.